Metaphysics

I. Definition and Key Ideas

Metaphysics is the most abstract branch of philosophy. It’s the branch that deals with the “first principles” of existence, seeking to define basic concepts like existence, being, causality, substance, time, and space.

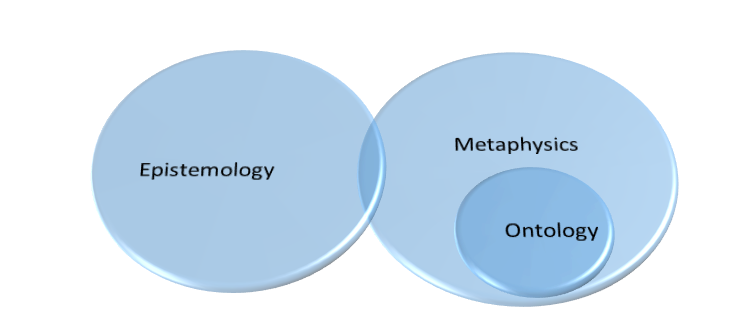

Within metaphysics, one of the main sub-branches is ontology, or the study of being. These two terms are so closely related that you can often hear people use “metaphysics” and “ontology” interchangeably. Many of the concepts raised in this article are about ontology, because this is one of the most active areas of metaphysics. However, the two concepts are not exactly the same: whereas metaphysics studies the general nature of reality, ontology specifically studies the idea of being. Another way to put this would be to say that ontology asks “what” while metaphysics asks “how,” although this is only a generalization.

II. Metaphysics vs. Epistemology

Whereas metaphysics is the study of reality, epistemology is the study of how we come to know reality.

| Metaphysics | Epistemology |

|

What is causality?

What is time?

Is there such a thing as free will?

What is a substance?

|

How can we know whether one thing caused another?

Is time part of the structure of reality that we experience, or is it just part of the structure of our own minds?

|

There are many questions that fall into the overlap between metaphysics and epistemology. These are mainly grouped under the heading of philosophy of mind, the sub-field of philosophy that deals with how minds work, what they are made of, and how things like perception, calculation, and moral reasoning work at the cognitive level.

III. Famous Quotes About Metaphysics

Quote 1

“Why are there beings at all, instead of Nothing?” (Martin Heidegger)

This is one of the most basic metaphysical questions, and has been raised by several philosophers in the Western tradition. Several answers have been offered, notably the idea of a god who creates existence for the same reason an artist creates a sculpture – for the joy of creation.

However, since the development, during the twentieth century, of the philosophies of phenomenology and its later form, existentialism, most philosophers have looked for answers based on things that we can know for sure rather than faith or wishful thinking; the phenomenologists and existentialists base their metaphysics on the observation that the only thing we can know for sure is our experience, and therefore they take the existence that we experience, or phenomena, as the first fact of metaphysics and go from there.

Some philosophers argue that the quote shown above isn’t even a meaningful question. To them, the existence of “something” is logically necessary for a being like Heidegger to ask the question: therefore, if the question is being asked, then there necessarily must be something rather than ”Nothing,” and thus the question is pointless. Think of it this way, you cannot ask a “Nothing” why it’s not here (or any other question for that matter), and therefore you cannot receive an answer if it doesn’t exist.

Quote 2

“Shallow men believe in luck or in circumstance. Strong men believe in cause and effect.” (Ralph Waldo Emerson)

Metaphysicians frequently ask what causality is and even whether or not there is truly any such thing. Some philosophers are extremely skeptical about causality, arguing that all we can ever know is that something happened and then something else happened. We’ll never truly know if there was a causal link between them, or if it was just a coincidence, or if some third event happened which was the real cause. Emerson, in this quote, is showing his colors as a pragmatist, or someone who believes that truth is whatever works, practically—and that being practical enables human beings to live well. In his view, since causality is true practically speaking, men with “strong” minds believe in it, as opposed to believing in luck, which is a matter of faith or wishful thinking.

IV. The History and Importance of Metaphysics

Metaphysics is such a broad field that it’s hard to say when it started. The word “metaphysics” comes from Aristotle, but he was certainly not the first philosopher to raise metaphysical questions. Long before Aristotle was born, early Greek philosophers were developing all sorts of metaphysical and ontological theories: for example, the theory of the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire) is an ontological theory and therefore it belongs in the category of metaphysics.

Similarly, all major religious traditions addressed metaphysical questions at one point or another. Islam, for example, has an elaborate metaphysical system based on a single “first principle”: the unity of god, or tawheed. Starting from the idea of tawheed, Islamic philosophers have used rational deduction to work out all sorts of philosophical conclusions that continue to be debated around the world today. Similar traditions exist in Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and of course Christianity and Judaism. Confucianism is the one major religion that doesn’t focus on metaphysics (Confucianism is more of an ethical-social doctrine than a metaphysical one), and for this reason some scholars argue that it shouldn’t be included within the category of “religions” at all!

The Scientific Revolution had a far-reaching impact on the way we think about metaphysics. The early scientists figured out that they could understand the world much more effectively by only believing in ideas which could be tested and thereby proven. Many people today unfortunately misunderstand and think that science is a faith in the material world and a denial of any immaterial world. This is not correct at all. Many scientists do believe only in the material world, but that’s only because it’s difficult or impossible to test and prove ideas about the immaterial world. And if you believe in something that cannot be tested and proven, then how can you know if it’s really true? Nevertheless, many of the world’s greatest scientists also believed in a spiritual world, including Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein.

In any case, once the scientific method was introduced it became obvious that you can’t be sure of anything beyond the degree to which you can test it, so many people since that time have rejected faith.

And now, since the development of quantum physics at the beginning of the 20th century, some scientists have been trying to develop a new “metaphysics”—because physical reality at the quantum level is quite different from anything anyone imagined previously–and unfortunately impossible to understand in everyday terms. Right now scientists do not in general agree on what quantum physics tells us about the metaphysics of the world and there are many competing interpretations; but what they do know is that the rules of quantum physics make incredibly accurate predictions about what actually happens in nature—much more accurate than anything that came before–so any metaphysics which is not at least consistent with quantum mechanics is probably wrong.

V. Metaphysics in Popular Culture

Example 1

The Matrix raises many philosophical questions. Most of the questions are epistemological (e.g. “how would we know if we were living inside a computer simulation like the Matrix?”), but a few are metaphysical (e.g. “what would happen to the body if the mind suffered an injury in the Matrix?”) At one point, Morpheus says that “the body cannot live without the mind,” but is that really true? The answer depends on what “the mind” is and how it relates to the body, and these are complex questions that metaphysicians have been working on for centuries.

Example 2

“In the beginning, there was nothing, which exploded.”

(Terry Pratchett, Lords and Ladies)

This is a line from the comedy writer Terry Pratchett, whose works often get their humor from philosophical puzzles. In this case, the question is “how can nothing explode?” On one level, it simply doesn’t make sense. However, since there is very strong evidence that the Big Bang did in fact happen, the statement is worth considering. A dedicated metaphysician might try to make sense out of the idea by raising questions about what “nothing” really means; it’s a more complicated concept than it appears at first glance, and philosophers have raised questions about whether it’s even a coherent concept at all!

VI. Controversies

Dualism vs. Monism

Given that metaphysics is such an old field, it should come as no surprise that it has many long-running controversies. One of the oldest is between monists, who believe in a single kind of substance in the world, and dualists, who argue that there are two. “Substance” is an idea from ontology, which basically means, “what anything is made of”; so this debate is about whether everything is made of matter, or everything is made of mind–or other possibilities!

Dualists differ widely in the specifics of what basic substances they believe in. Each of the following pairs has a school of dualism associated with it:

- Matter and mind

- Good and evil

- Yin and yang

A dualist would pick one of these pairs and argue that all of reality is made up of those two substances: for example, if you’re a mind-matter dualist, you see everything as made up of either matter or mind, or some combination of both.

Monists, similarly, focus on different substances, but they all argue that a single “thing” makes up the world:

- Matter (materialism)

- Thought (monistic idealism)

- Atman (Hinduism)

- Tao (Taoism)

To a materialistic monist, everything in reality is made of different forms of matter; they don’t believe that “mind” is a separate substance. Similarly, classical Hindu and Taoist philosophies see all of reality as an expression of a single ultimate reality called Atman or Tao.

Metaphysics: is it a waste of time?

Although metaphysics has been around for as long as philosophy itself, many philosophers have questioned whether it actually makes any sense. Ludwig Wittgenstein, for example, argued that the metaphysical was beyond the reach of human language, and therefore that it is futile to try and “describe” it as philosophers typically do. Instead, Wittgenstein argued, you had to approach metaphysical truth through other means – though he never specified what those might be. Music, art, and religious ritual are obvious candidates, since these are techniques for experiencing metaphysical truth without describing it in language.

Similarly, the pragmatists argued that metaphysics is too vague to succeed in its task. For them, words like “existence” and “causality” are just vague abstract ideas that human beings use to get by in a complicated world; since they cannot be taken apart and defined in terms of more basic ideas, they have no philosophically rigorous meaning. Thus, metaphysics is a futile practice (a waste of time) in which philosophers are just playing with words and meaning, but not talking about reality.

On this view, particle physics and quantum physics work better than traditional philosophical metaphysics, because these scientific fields don’t rely on the clumsy apparatus of human language. Instead, these scientists use mathematical reasoning, a much more precise tool that enables them to avoid Wittgenstein’s critique. The problem with them is that nobody yet knows how to interpret the mathematics physically; they just know that it works.

Despite these criticisms, a small group of dedicated philosophers and scientists continue to raise questions about metaphysics, just as they have done for thousands of years.