Argument

I. Definition

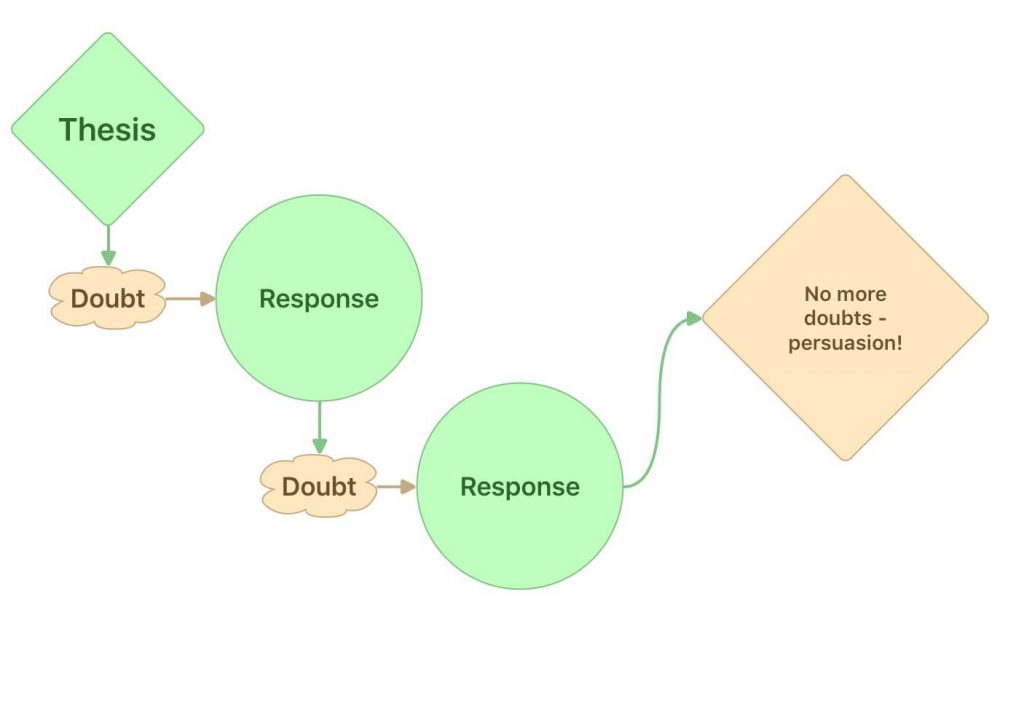

An argument is a series of statements with the goal of persuading someone of something. When they’re successful, arguments start with a specific point of view, something that the reader doubts; by the end of the argument, the reader has been convinced and no longer doubts this view. In order to argue well, you have to put yourself in the reader’s position and imagine what doubts they might have about your claim.

Argument is not the same as fighting!

From watching political debates and sports analysis on TV, you might get the impression that arguments are hostile and aggressive, more intended to defeat the opponent than to persuade anyone. But this isn’t necessarily true. In fact, the best arguments come from a place of sympathy and friendship — when friends have differing points of view, they may explain the reasoning behind their view as a way of building understanding. Often this takes the form of a friendly argument or debate.

In fact, learning to argue well is one of the most important skills you can develop — in your personal and professional relationships, a certain amount of conflict and disagreement is inevitable. If you don’t know how to argue with reason and logic, then all you’re left with is fighting. An argument is all about coming to an agreement (or, if agreement is not possible, at least understanding the reasons why it’s impossible). Fighting, on the other hand, is all about expressing emotions like anger and hurt, without caring about the other person’s point of view. Argument, if you know how to do it right, can resolve differences; fighting usually just makes them worse.

II. Types of Argument

There are three basic types of argument: deductive, inductive, and mixed. They are based on three different types of inference (see next section for more on what an inference is). If you find this confusing, visit our article on Inferences for more detail.

- Deductive arguments are built from deductive inferences

- Inductive arguments are built from inductive inferences

- Mixed arguments are built from both types of inference

So what’s the difference between deductive and inductive inferences?

Deductive inferences have to be true. You start from a basic statement or “premise,” and as long as that premise is true there is no logical way for the conclusion to be false.

Examples

- If x=y, then we can deductively infer that y=x. There’s no way for that not to be true!

- If Socrates is a man and all men are mortal, then Socrates must be mortal as well.

You could always question the premises of a deductive argument (for example, you might say that Socrates is a god, not a man, and therefore question whether he’s mortal), but if you accept the premises you have no logical choice but to accept the conclusion.

Inductive inferences don’t have to be true, but probably are.

Example

For the whole history of human experience the sun has risen in the east and set in the west; therefore, the sun will do the same thing tomorrow.

This is almost certainly true! Most people would readily accept this line of argument. However, notice that it’s a matter of probability, not a matter of logical certainty like a deductive argument. After all, it’s possible that aliens could come and destroy the sun, meaning it wouldn’t rise or set ever again. That’s extremely unlikely, but not logically impossible.

So, in strict logical terms, deductive arguments seem stronger than inductive ones. However, inductive arguments have one crucial advantage: they usually matter more. In our day-to-day life, almost all of our decisions are based on inductive inferences:

- It usually takes me an hour to get to work, so if I leave at 8:00 I’ll probably get there by 9

- Yesterday I got sick after eating Wendy’s, so I won’t go there for lunch today

- My best friend advised me not to skip class, and her advice is usually good, so I’ll follow it

These inferences are all inductive — they’re all based on reasonable probability, not absolute logical certainty.

Deductive arguments, on the other hand, are based on absolute certainty, but their conclusions are often trivial:

- y=x, so therefore x=y. But who cares? These are just different ways of writing the same equation. The first statement might be very important: y=x might be the key to solving an important algebra problem. But the deductive argument doesn’t provide any new information on top of what we already started with.

- I am a human, and all humans are primates, so therefore I am a primate. Again, does this really matter? The statement “all humans are primates” is certainly interesting in its own right, but does “I am a primate” really add anything new on top of it?

III. Argument vs. Claim vs. Inference

In short, an argument is made up of claims connected by inferences. Each individual step in the argument is a separate claim. There’s a main claim, or “thesis,” which is supported by supporting claims. As we saw in section1, the supporting claims are intended to respond to doubts about the main claim.

Inferences are usually not stated out loud; they are invisible connectors between the claims in the argument.

Example

Think about a cover letter. A cover letter is your chance to persuade someone that they ought to hire you — it’s a kind of argument that people in nearly every line of work have to master. A cover letter might work like this (the underlined portions would be stated explicitly (claims), whereas the italic parts are just implied/anticipated (inferences)):

Thesis: You should hire me.

Expected doubt: We need someone with statistics skills, which most people don’t have

Supporting claim: I studied statistics in college.

(Hidden Inference: when people study something in college they gain skills in that subject)

Expected doubt: OK, but studying something in college doesn’t mean you can apply it

Supporting claim: I also did a market-research internship during the summer

(Hidden Inference: real-world internships teach people to apply their knowledge)

And so on. In the cover letter, each paragraph covers out one of the supporting claims, providing further support and detail. In the end, if you’ve correctly anticipated your reader’s doubts, you will persuade them that you are the best person for the job!

IV. Quotations About Argument

Quote 1

“I find I am much prouder of the victory I obtain over myself, when, in the very ardor of dispute, I make myself submit to my adversary’s force of reason, than I am pleased with the victory I obtain over him through his weakness.” (Michel de Montaigne)

The French essayist Montaigne had a talent for argument, and understood the importance of listening to the other person’s point of view rather than just trying to defeat it. In fact, this quote is a pretty apt summary of the difference between argument and fighting — when you argue, you always remain open to the possibility that you will be the one persuaded in the end, rather than just hanging on to your side no matter what.

Quote 2

“There can be no progress without head-on confrontation.” (Christopher Hitchens)

Another master of the art of argument, journalist Christopher Hitchens was an outspoken proponent of various controversial views, from politics and religion to science and literature. In all of these areas he emphasized the importance of arguments and logic, not because he was an inherently contentious man (though that may have been true — opinions differ), but mainly because he believed that the clash of ideas would lead to new, better ideas.

V. The History and Importance of Argument

Arguments are probably as old as language itself. In fact, it’s possible that language originated as a way for pre-human primates to influence one another’s behavior without resorting to violence. Imagine you’re a homo ergaster on the African savannah: you want one of your group-mates to help you search for berries, but she’s more interested in grooming. Wouldn’t it be helpful if you could reason with her and persuade her to spend her energy in a different direction? It’s possible that language evolved as, among other things, a tool for persuasion.

However it started, argument is an extremely widespread human behavior. Different cultures have different ways of going about it — different ideas, for example, of what counts as polite argument, or what sorts of topics are appropriate to argue about in a given setting. But all human beings, across the globe, use language to make claims, express doubts, and respond to those doubts.

While some rulers try to suppress argument, others historically have welcomed it. For example, the Mughal Emperor Akbar was a Muslim who ruled India from 1556-1605. He knew that his people followed many different religions and philosophies, and built temples and schools for the specific purpose of staging reasonable, enlightening arguments among all faiths and points of view. His hope was that, through argument, people of different religions would learn from each other and that eventually a new religion would emerge, combining the best insights from each tradition.

In Europe, a short time later, this sort of argument fueled the Scientific Revolution and later the Enlightenment. Drawing on the ideas of non-European thinkers in places like India, China, and the Middle East, Europeans developed a method of argument and experimentation that we call science. They also began to consider new forms of government based on arguments and persuasion rather than royal decrees and birthright — thinkers like Benjamin Franklin, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Thomas Jefferson conceived of a government founded on constant argument, both in the public square and in institutions like Congress.

VI. Argument in Popular Culture

Example 1

Sports shows provide great examples of both arguments and fighting. They usually start with a controversial thesis like “Aaron Rodgers is a better quarterback than Carson Palmer.” Then the two hosts will argue back and forth over whether the thesis is true or false. Sometimes, they will listen to each other, anticipate the doubts of the other side, and respond to them rationally; other times, they just shout over each other and never make any progress towards persuasion, in which case it’s an example of fighting rather than argument.

Example 2

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, this is Chewbacca. Chewbacca is a Wookiee from the planet Kashyyyk. But Chewbacca lives on the planet Endor….If Chewbacca lives on Endor you must acquit!” (Johnnie Cochran, South Park)

This line from South Park is a spoof of the real Johnnie Cochran, the lawyer in the O.J. Simpson trial, but it’s also an example of a (terrible) deductive argument. The argument is structured like this:

- If Chewbacca lives on Endor, you must acquit (find my client not guilty)

- Chewbacca lives on Endor

- Therefore, you must acquit

Statement #1 is clearly an absurd premise, but if it were true then this deductive argument would have the force of absolute logical certainty. That’s the problem with deductive reasoning: if the premises are accurate, it’s air-tight; but often they are not.